Quarter After Eight Table of Contents

Robert J. Demott Short Prose Contest

Each year during the month of November we welcome contest submissions for prose—of any genre—under 500 words. This year, David Haynes served as contest judge. We’re pleased to share the following pieces with you.

Winner: Girls Are Always

Allison Field Bell - Creative Nonfiction

Doing things in cars with boys. Not all girls, not all boys. But I am always. I was always. This moment for example. I am in the back of my car, the beat-up Volvo station wagon my mother passed down to me when I turned sixteen. I am in the back of my car, and there are tan leather seats with worn spots like wrinkles where sand accumulates from my drives to the Pacific.

I am in the back of my car with a boy. A boyfriend. And we are on a residential street in Sebastopol parked uphill along an arc of a curb. There is a streetlight I stare at from the window behind the driver’s seat. The streetlight is a rotten golden color. Street- lights remind me of cities, especially New York. And suddenly I am thinking of the Ninja Turtles. Or maybe it’s Batman. Some bad-guy fighting city-dwelling character from my childhood.

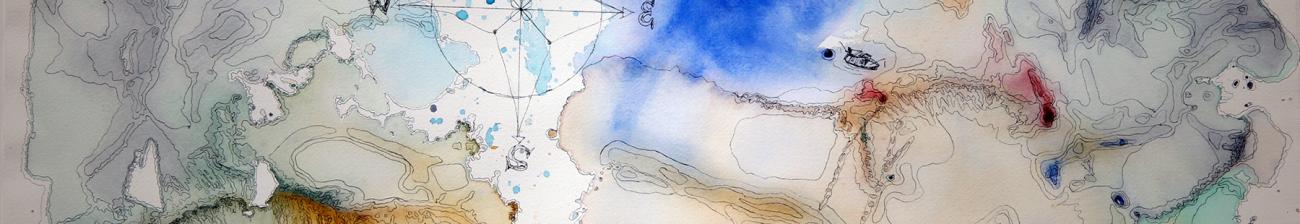

Except my childhood never really ended because I’m still laying here thinking of animated men while my boyfriend unbuttons my jeans. He slides them down only enough. I am still staring at the streetlight. There is that familiar pain and then he feels the inner part of my thigh with his hand, pauses. I imagine what he feels: raised lines, sweeping arcs in my flesh. Like a topographi- cal map of self-destruction. I don’t know how things progress from there. I know the bits of sand stuck to my skin, a vague ache where his body weighs down the loop of my jeans so they dig around my knees. There is a streetlight, and I can feel it snap and shudder against the night. And then he is pressing hard at the thigh with his body, cupping the side of my jaws with his hands. “Don’t do this anymore,” he says. “I’m not trying to fuck Frankenstein,” he says.

I don’t know what I say then, but I can’t stop with the streetlight. I think about how strong the glass must be. To weather storms and wind and sun. I wonder how and where the current comes from, who changed the bulb last. Do you even change streetlights like that? I imagine a large ladder. A man with his hands on the light source. A man fixing something bro- ken. A man with gentle hands. A delicate untwisting. A bright yellow light.

First Runner-Up: The Friend

Olivia Zubrowski - Fiction

Paul lives in an old farmhouse that had to be moved three miles south on a flatbed truck when the interstate was built. The nearby highway sings, especially in winter.

One day in November he is in the attic, looking through boxes of photos. They brim with seventy years of blurry, dark pictures, many of people he does not know. He is holding a picture of a July family reunion—one he remembers as clinging in fear to his mother’s dress—but in this picture he is smiling. Perhaps the patterned fabric of her dress transposed itself onto another memory: a new life is forming inside of him, a parasite, using the same fear and sharp joy as the old. Particularities of memory singe and cross. Does the former order matter?

The attic is still. Cold slips through the old windows.

There are a few copper leaves left on the tree outside. They are curled like a hand, or a goddess. When he was small, he went to a museum with his mother. Transfixed by the dim and quiet, his attention became syrupy and slow over the ancient jewelries from Greece, Rome, Egypt. When he turned around, the room was filled with people he did not know. The small window at the end of the gallery showed the lapis of nighttime. He cannot remember how he found his mother.

A small gray hand emerges from a pile of quilts to his left.

The hand pulls a tiny, broken body into view: an apple-sized head with wrong-put eyes, listing, a crooked neck, two muscular legs, soft gray fur. It is almost human. The right eye swings to look at Paul.

When he was five, in the backyard of this same house, he saw a snake swallow a toad whole. Four black eyes blinked and two did not, and he ran through the twilight grass to tell his mother. When he got to the porch he could not get the words out. You’re too old for this, he remembers thinking.

The creature follows him in irregular beats down the stairs and into the indigo kitchen. Paul opens the fridge. Light cuts across the floor, and the creature heaves towards it. Paul watches the creature’s ragged back move, too quickly, its small-right- hand-paw kneading the cold tile. There is something wrong with the creature’s left arm.

Paul’s fingers drag like a loose net through the fridge. He offers the creature scraps: a bowl of water, a leaf of lettuce, a crust of pizza. The creature eats all of it. The creature does not look up at him. When he wrings an apricot in two, reaching the pitless half to the creature, its small gray fingers wrench handfuls out of the asteroid-fruit. It is full of sweetness; it is mealy on his tongue. They sit in the moonlight of the fridge, sharing fruit, until the creature collapses into his open palm. He is surprised by the head’s weight, and how gentle it was when the neck broke.

Second Runner-Up: To the Rescue

Karen Hildebrand - Prose Poem

To the man in the news who pried a rabid bobcat from his wife’s shoulder with bare hands, Where are you? Where are you, with your concealed-carry permit registered to Happy? I am certain a man named Happy would never address me as Poochbelly Karen, even behind my back. I am certain Happy would give Poochbelly Karen a kidney without so much as a pause to check his wallet, should she have to ask. What is wrong with me? No one to carry a plate of brownies, no hand to bite when mad with grief.

Finalist: We Don’t Two Step No More

Negesti Kaudo - Prose Poem

& last night Avery says to me that my daddy is doing the ancestor’s work & since I don’t believe in much I hold onto that because this morning the sun broke through the clouds again & I am feeling something regal in my veins. My heartbeat is elevated but maybe that’s the high blood pressure talking or last night’s impromptu grief dance party still working its way through my system & we found a way to have a great time playing throw- backs without listening to that r*bert k*lly bullshit & found a way to three-step around my grief in a contemporary waltz where for a minute I forgot that I was supposed to be creating not suffering, thinking not procrastinating. For a minute my responsibilities flew from my fingertips as my arms swung from the windows to the walls surrounded by that pitch black almost winter solstice darkness & all the pent up energy grief lust anxiety leaked through my pores. Maybe the ancestors realized I needed a break & so they baptized me with debilitating grief for one day, an important day, my daddy’s birthday, where I was dancing not crying under a full moon in Gemini at the edge of the Illini prairie.

Finalist: Bugs Bunny

David Renteria - Fiction

My dad had been a carpenter in Sacramento for a year when my mom decided we should join him. The weeks after we’d arrived, I spent the meat of my days working with him as his garbage boy. We would wake up in the placenta gray of dawn; it was summer, the sun would eventually open its mouth and hound us into cover, but the days were always cold before anything else. If my mom was up early enough to make breakfast, she asked my dad what his day would be, where the job was, when he’d be home.

Otherwise, he was quiet, and I knew to be in the passenger seat by the time the truck’s engine turned over.

One day he asked me what I wanted for lunch. In Mexico I’d watched Tatiana, a show about a pretty lady with a purple skirt and stars on her cheeks. Once, on the show, a person in a chicken suit came on and told us to eat at Quentoqui Frai Chiquen.

I told my dad the name. He said ok, and we drove to a square white restaurant and got in line for the drive-thru. My chest tightened at the difference between the boy-voiced, laughing white chicken I remembered, and the business—with hazy windows, on an asphalt lot, with impenetrable U.S. customers— I saw through the windshield. I asked my dad if he was sure this was right. Si, he said, and pointed at the first big letter painted crimson on the restaurant’s side. Quentoqui, he said. Then the next letter. Frai, he said. And the last letter. Chiquen. The name I’d heard on Tatiana had not been a name, but English.

I looked out my window, away from the menu. I resigned myself to the embarrassment of having to ask ¿habla español?, our charades at the register if they didn’t. It was the barrel my mom and I stared down whenever we bought McDonald’s.

The moral that I should only ask for places with names that I understood burbled in my head. We pulled up to the drive-thru speaker. It garbled out gibberish that sounded like it came from deep underground. My dad said some noises back, cut into the same length and tones as the speaker’s. We moved along.

At the window a pale black-haired lady in uniform opened and closed her mouth and my dad handed her some cash. She gave him two white boxes in a thin, see-through plastic bag, which he handed to me. He got us back on the road. I waded through the bumps of our moving truck to confirm that the bag really had pollo frito y papas, that my dad really had ordered food, from Americans, in perfect English. He noticed my eyes on him, and gave me a slight smile, his brow still furrowed, his day still ordinary, not knowing that was the first time I clung to him.

Finalist: Foreclosure

Claire Robbins - Creative Nonfiction

I have lived in two cities: Kalamazoo and Tegucigalpa, both named in languages wiped away by colonizers. The name Kalamazoo may mean boiling water, or its meaning may have been lost or distorted by white colonizers. One of the possible meanings of the name is mirage. The name Tegucigalpa may mean silver hill, or it may mean a place where royalty lives, a place of sharp stones, a meeting place, or colored rocks.

Tegucigalpa is the capital of a former Spanish colony. Some buildings were so old that the glass was thicker at the bottom of the windowpane because the amorphous solidity of glass allows it to slowly melt over time. Later I would learn this is a lie told by tour guides to exaggerate the city’s age. Glass is an amorphous solid, but renaissance glass making produced uneven panes, and the windows were stronger with the thick side placed at the bot- tom of the window. The windows were not old enough to melt.

As a child, I played along the shore of Lake Michigan, and I knew the lake could kill me. I slowly poured wet sand from my hands to build drip castles. This was on land stolen by my ancestors five generations before my birth. I knew to swim parallel to the shore if the current pulled me away. Some indigenous land rights activists advocate for granting legal personhood to bodies of water.

We moved to Tegucigalpa because my father taught at a bilingual Christian school and brought my family along. I don’t know what motivated my parents to move from Kalamazoo.

As a teenager, it was an adventure. Then the scales fell off my eyes, and I saw the triple horror of whiteness, Christianity, and capitalist exploitation, like a three headed serpent attacking Central America, only it wasn’t a serpent, it was us.

Back in Kalamazoo, the paper on the exam table crinkled underneath me. The doctor seemed rushed as he handed me two pills and a paper cup of water. I spent $475 of my federal student loans on those pills because Medicaid in my state did not cover abortions. Then I had a baby because I couldn’t afford another abortion, and I couldn’t find a birth control that worked for me. Like Lake Michigan, I drowned some children and spared another at random. I was a force, a rage, I was a glass lake.

Now when I walk in Kalamazoo, I pass by two cities, the city I see in front of me and the city I remember. Walking south on Burdick Street, I pass an empty lot that once held a house where I slept some nights. The house belonged to a friend before it went into foreclosure and the city tore it down. There are gaps in my life too, where nothing stands but memories or possibilities. I want to imagine what could have been and write myself a future free from the violence of the past.

Finalist: One Must First Establish a Relationship with the Reader

Josh Bell - Fiction

- Dear Reader, you seem to not have shaved anything, not anything at all. You walk around out there, thinking you’re not trapped in a box. When you think you’re being stealthy you sound like a marching band thrown down the stairs. When is the expiration date of your eyes always on me? Again and again I am placed in the holy light of calendars. Couldn’t you look at anything else? When was the last time your feet did not touch the ground because your father lifted you? Don’t act like you love me. Don’t act like you had a father.

- Dear Reader, if you like plot it means you are afraid to die. Sometimes I lie and say to you that I have never read a book that I have, in fact, read. And this is because I know there’s a good chance, thinking that I have not read that book, that you will read that book to me, aloud, for my edification, all night long.

- Dear Reader, whenever you read to me, in my mind I put on the smallest dress. I do not want to die wearing this fast food restaurant t-shirt I’m wearing. Not like my fathers and my father’s fathers. The hand jobs, in those days, were never elective. You said to me once that you were sad. We were out in your back yard, watching the bounce house deflate. Again the birthday party had been planned on the wrong day. So here’s my only advice, which works for any situation: close your eyes, like I do, and think about the saints.

- Dear Reader, when I met you in the forest you were afraid of the forest. Bird feathers clumped around your exit wound. You and I, so quick, had a baby. We planned a succession of birthday par- ties for that baby. It was standing over there. God, it even looked like a baby. I tried to hold your hand but, as always, your foot got involved. I was on the wrong side of history. When I said “two peas in a pod” you pretended to think I said “two Petes.” It was August, and there wouldn’t be anything left to love by September. It was the summer of two Petes, one of whom had your phone number, one of whom has your rain slicker. “When will we ever tell the same lie?” you asked me. Come back, dear reader, you sweet romantic. I’m your own true system. No longer will I speak ill of the dead.

Fiction

Please Continue to Be Patient - Leah De Forest

For breakfast that first morning I swallowed the piece of gum I found in the stupid lady pocket of my work pants. The gum was fruit-flavored, watermelon if I had to guess; calorie-fucking-free. After a night on hard dirt among disoriented, irritating humans who’d farted and wept and shuddered in their “sleep,” I was ready to be up and active.

There was also a degree of gum-guilt involved.

The sky was a hot orange, about twenty minutes before sunrise, crisp heat crackling in my sinuses. There were about two hundred of us evacuees inhabiting the rest area in a fairly random fashion. I mean, we were hemmed in by a tall temporary fence across the exit road and a ring of parked buses and police cruisers behind us, but within that: not a lot of structure going on. Over time, we would become—not so much organized, as fractured into clumps. But this was the just first morning.

Happily, I had only to step over about twenty ad hoc sleeping forms before I found what I was looking for. A teacher-looking type, curled up alone, with one of those mini water bottles clutched in her fist. She offered no resistance.

I drained the bottle in a few gulps.

When it all started I’d been at my reception desk, headset straddling my skull like a smile. “Please hold,” I chirruped into it. “I will direct you momentarily.” I don’t mind admitting that I hated that job, absolutely spittingly despised it, but in this economy, what are you going to do? Spend your waking hours wearing too-tight pants behind the reception desk at a mid-sized biotech that specializes in anti-aging treatments, that’s what.

So, I was working away on my Wednesday tasks when things began to rumble, pens sliding off desks and windows whooping in their frames. We were directed towards the exits and the waiting buses that had been arranged for us fortunate few, since through some sort of sciencey magic they’d been warned. It was their priority, they told us repeatedly, to get us to safety.

They succeeded, I guess. The fires and blackouts and collapses hit the ones left behind.

As an experience, I can’t say that I recommend the events of that day. The truth is I felt utterly hopeless. But doesn’t every pop psychologist and annoying aunt say it’s important to focus on the positives? Practice gratitude. So how about this: those buses had some comfy seats. Deep red velour with fine blue stripes. I can still feel the shorn softness against my fingertips. On a slightly less positive note, I was seated next to Janine from Sales, who clearly wished she was sitting with her work husband, James, but was too uptight-polite to admit it. On she went on with her usual chatty shtick about my skincare regime. Her voice got these little sharp upticks in it. Jesus. I stuck my Air Pods in and pretended to be listening to a really smart podcast about politics.

The traffic was just starting to bank up on the freeway when a cordon of cops waved us out of the right lane and into this Vista Views rest area. We got out to stretch our legs, explore the parking lot/nature and use the limited bathroom facilities. There was one busload full of baby boomer music festival goers, all long gray hair and rumpled green T-shirts with CityMusiCMoveMent across the pectoral/tit area. They were dressed as you’d expect, low-crotched pants and idiotically kind smiles. Another bus contained most of the staff of BioMoodMed; one bus had what looked like a charter school group on it (I would later learn they were community college freshmen on their way back from vol- unteering at a soup kitchen, hence the matching red polos); an- other, a bunch of white dudes in suits (management consultants mostly). The fifth bus was half-full of city sanitation workers who spoke in low voices and laughed more than was comfortable. There were also some genuine randos in there, people who were walking past when the buses were loading. Among them was one girl child. She moved sharp-like among the crowd, eyes wide with unaccustomed attention. I felt her, you know? Under the pressure of all those stares.

I stuck with my colleagues, not because I liked them but I guess because my chimpanzee brain was trying to keep me safe. This turned out to be a boring choice. A debate erupted about managing the collective charge on our phones. The networks had been down since we left the city, which was not unexpected, nor was the fact that constantly searching for service was going to hasten battery death. I was willing to bet that some people (Janine) had packed portable chargers and at that point it seemed likely we’d all be back online soon, so I really wasn’t into the heatedness. True, it would’ve been best if the group agreed on a roster: one person could leave their phone on for say thirty minutes at a time, so we’d know if the network came back up. But what, Alicia from Accounts asked, if some networks came back and others didn’t? How would we know then? It became clear that we each wanted to be the one who left their phone on and also be the one whose battery lasted until there was an opportunity to charge it again. Therefore, no cooperation was to occur. Given the circumstances, this shouldn’t have been surprising. And yet it was. For a few seconds we all had our eyes open a little wide, eyebrows raised. Like, huh.

I’m plenty addicted to my phone (Candy Crush ftw!), but the truth is I didn’t much need it for connection with other humans. My family was back East, having gathered on the Vineyard for Grandma’s eighty-fifth birthday, where they ate too much Whole Foods cake and talked about everyone’s careers and babies (Auntie Kay had posted liberally about it on Instagram, #grateful). Given the glee with which I’d delivered my You’ll have to party without me RSVP I didn’t expect to hear from anyone soon, unless they wanted to know if I was dead or not, and I’d already marked myself safe on Facebook before the network fritzed. I did have a few new friends who weren’t absolutely ambivalent about my welfare, but they all had small children. It’s a truth universally acknowledged that once people reproduce, their ability to give a shit about anybody else’s anything is significantly reduced. I admit to some petulance about this. A few years back I tried to get in on the experience, blaming some (fictional) failing contraception for a (fictional) unplanned pregnancy. Unfortunately I let the lie go on too long, into the fifth month. Fuck me though if it wasn’t warm in the glow of all that texting interest. What are you doing to do, how are you feeling, is there anything you need. Screw that deadbeat guy, you’ve got this. There were even casseroles. Chicken! Garnished with parsley! It was all fun and love until my friends dropped me. In the three years since I’d been rebuilding, volunteering at library story time, and briefly joining a local singles group. I wasn’t in it for sex, but for female friendship.

Given my feelings about women who reproduce, you might be surprised I want them as friends. Well, I’m drawn to them. Also, they’re socially handicapped, unable to get out much and subject to social pressure to model friendliness for their offspring (even when said offspring are too small to notice anything beyond their own slimy fists). Such women are sufficiently open to conversation that we can get past the usual barriers (viz., my face). These new friendships were still a few months shy of the search-for-you-in-a-disaster phase, but I thought my evacuee situation might speed things up. Pity = something to talk about = warm feelings.

But anyway.

I don’t think any of us saw that giant fence coming. We’d been at Vista Views for almost an hour, milling around and squinting at the sky and the struggling trees, trying to see if we could get a clear look at the city (we couldn’t), when a couple of guys showed up with a tow truck. They pulled this tall temporary fence across the mouth of the parking lot. A ripple of what-the went through the crowd. Some cops stepped in front of the fence and megaphoned at us to wait.

I wasn’t the only one freaking out. Janine sweated through her pink Oxford shirt and James was rubbing his temple so insistently that thin smears of blood sprouted along his hairline. Janine had two little kids and an actual husband somewhere out there (James just brought coffee and expressed an interest in her weekends) and as she kept semi-shouting at the cop who had the misfortune to be semi-nearby, she needed to know if they were okay. I couldn’t help pointing out to Janine that she might find it helpful to show some concern for the actual child sitting in the dust right over there, and she said, “Pardon me?” in that menacing tone people get, so I arranged my face accordingly (even smile, downward pressure across the brow). One of the community college kids—he was cute—came over to ask if I was okay. He called me miss.

“Don’t worry about me,” I said. “I’m used to it.”

The kid (his name was Colin) stood a respectable distance away and racked his brain for something to say. Soon enough we got separated by a bunch of MusicMover boomers swaying together in some sort of mutually supportive (?) motion. They weren’t singing, at least. I remembered that kernel of wisdom from—oh yeah, it was Kimmy Schmidt, the Unbreakable one from Netflix—that a person can endure anything in ten-second increments. I breathed slowly and adjusted my poorly designed purse (why do they make women’s everything so goddam small?) on my shoulder. It was another twenty minutes before one of the cops— short, stocky enough that you wouldn’t fuck with her—raised the megaphone back to her mouth. Now, I can’t be assed doing the math, but that twenty minutes represented a lot of ten- second bits. Thirst was making them feel extra long. I hadn’t brought my water bottle (what did they mean, telling us not to stop to bring anything on the buses? And what was my problem, actually listening?). The cop cleared her throat and the sanitation workers ambled up closer to the fence, as if: what? It was about to slide open? My officemates frowned officially at them (something about business-casual attire makes people feel they own the rules, I don’t know). There had been, the cop announced, a delay. The buses would stay off the road for a short time. We would need to be patient.

This could have meant a number of things. As I said to my office-mate Frank (who had just then sidled up, too close), for a start, it represented a failure of infrastructure planning.

“I mean,” I said, “at the very least they should’ve anticipated that a city built on a fault line would require roads that can handle a mass evacuation. During Katrina almost five hundred people died in their own houses. Drowned or crushed, I guess. Meanwhile Canada can move thirty-five thousand people to save them from wildfires. I mean come on. Where’s our American ingenuity?”

Frank nodded, clearly hoping to formulate a clever response.

“In this case, unfortunately,” I went on, “we’re looking at a lot of deaths. Either on the road out there: perhaps there’s been a massive pile-up. Or back in the city. Maybe even inside the Earth itself, I don’t know, some kind of quake or giant sinkhole that’s sucked people up.”

Frank’s eyes went rounder and he remembered he had to go ask John about stationery.

It was going to be a struggle, adjusting to this new real- ity. If we weren’t going to get back on the buses, we were … to stay where we were. Which was very nearly the definition of nowhere. A rest area with an undersized rotary in the center of the parking lot. Around that, a wide patch of earth cut through with random walking paths. A single (concrete) picnic table with a shaggy woman lying on top of it, and that kinetic-looking kid (wild red hair, denim shorts) bolting away from it. If this was the here where we were to stay, and we had no cell network, we could … sit? Talk? Scary-watch the cops? A group of us Bio- MoodMed-ers settled for shit-talking some bus drivers who had taken themselves off to one side to smoke and had, it was noted, been driving with a degree of recklessness that they had failed to follow through on when the cops showed up. Which is to say, at least two of the buses (ours, and the community college kids’) might have avoided the blockade. If the drivers hadn’t been such incompetent shits, that is. I made appropriate noises of agreement for probably ten minutes—the shared outrage was a warm hug— and then my guts began to rebel. Like, a big-time adrenaline-fueled explosion was on the horizon. I scooted to the bathroom.

You never really anticipate how the bodily realities of a situation like that—hunger, thirst, a thwarted need to shit— come to inhabit almost every corner of the experience. You’re so in your body, at the mercy of your emotions. I think I speak for a lot of us that day when I say that our dominant feeling was a shaky wow. Like you see terrible scary shit on the news all the time, and you know you’re supposed to have emotions about it— empathy etcetera—but the fear you muster is faint at best. You know you’re supposed to be quietly moved and driven to action, like you might donate twenty bucks to an emergency fund, but mostly what you know is, that isn’t happening to me. I’m sitting here on my sofa eating yogurt or carrot sticks or (on a good day) peanut m&ms, and I’m thinking huh and I’m thinking yum. Like I realize that makes me a massive disappointment as a human but I don’t think I’m so far outside of the norm. I could see it on a lot of the faces that day (especially in the bathroom line). Distress, obviously, fear, disbelief, I can’t believe this is happening to me. And then, get this: a little bit of excitement. Like, finally, this is happening to me. I’m the one.

Naturally enough, the toilet had no seat. Just a hard (warm) ring of metal that I was, I gotta tell you, enormously grateful to rest my desperate ass on. Under normal circumstances, I avoid public toilets. I have a horror of other people’s germs, and the specific smell of other people’s digestive systems—well, it’s been known to make me explode at both ends. (Yeah, sure, gross. As if you’ve never needed to shit and throw up at the same time, occasionally in public). Unfortunately for me, someone else had gotten there first: there was a lot of vomiting going on in the next stall over. Also some weeping. (The smell, in case you’re curious, was corn and vinegar and bad meat.) I would soon learn that the vomiter was the kid. Rose, her name was (is). She was in there without her momma, which I would later realize was not all that unusual for her, since for reasons known only to her, Rose Sr. had abandoned the picnic table and was at that moment scratching her initials into one of the perimeter trees. Rose Jr.. was about a week away from turning nine. She’d been on vacation with her mother in the city, and luckily/unluckily for her, they were passing by the management consultants’ bus when it was found that they had a few spare seats. “What else were we going to do?” Rose Sr. would say to me later.

Rose and I were in there for so long that people started banging on the doors. I moaned. She moaned. I passed her some toilet paper under the stall divider, and I saw how small and skinny her fingers were. Delicate, oh, disgusting were we, but eventually we were done and I helped her get soap from the dispenser (it was almost empty and required some brute force). She was small enough that I could rest my elbow on the top of her little red head, if I wanted to, but I didn’t. The sight of her sharp little shoulder blades did things to my heart; the dirt behind her ears made me want to weep.

“Thanks, lady,” she said.

I want to say she had a sweet lisp and missing front teeth but the big new ones were partway through, and they looked sharp.

“I’m going to find my momma,” she said, and I followed.

Rose had a fast-bobbing gait and a gift for laughing at things that definitely weren’t a joke (“I still can’t find my mother! Maybe she’s gone!”). When we found her mother near the big old tree, Rose stood placid as the cussing washed over. “I had to go to the bathroom, Momma. This lady helped me.”

I could tell Rose Sr. didn’t like me much, but mothers usually don’t. Okay, the ones I sucked up to at the library learned to tolerate me—but I did stuff for them. Like pretend to give a shit about the baby-spittle-balls in their thousand-dollar strollers. The kind of mother Rose Sr. was—older, less needy, alert to the world’s bullshit—hasn’t got much time for a person like me. I can be hard to talk to, for a start, by which I mean I’m a bit defective, by which I mean I’m a disappointment. But, you’ll say, it sounds like you do okay. All chirrupy at your reception desk. Well, my mother helped me get that job. And work is not real conversation, is it.

No personality needed.

Another thing that some mothers (including mine) find difficult about me is that I’m uncommonly beautiful. I realize how this sounds. You think I’m boasting, that gorgeous women aren’t supposed to realize how attractive they are. But I challenge you to explain how anybody can fail to notice the kind of attention I’ve been getting my whole life, especially on first acquaintance. People are dazzled. They go from my eyes (deep brown) to my nose (narrow at the bridge, softly pert at the tip) to cheekbones (they require no explanation) and mouth (symmetrically plump lips, orthodontically aligned teeth) and you can almost see the geometry calculation in their heads.

Like they realize if they folded a photo of my face, it would divide precisely. I’m a mirror image of myself. Between that and my appropriately proportioned breasts, butt, and waist, they think—you can see it dawning—that is one beautiful woman. I imagine you think I enjoy this attention. The truth is sometimes I do. Being a cisgendered, heterosexual, unusually beautiful woman has its advantages. I never want for sex with men, for one. Crowds have a way of making way. Old ladies say funny/warm things to me in department stores, like, “Darling, if I had a face like that…” And men are often—not always, but often—chivalrous. Like Colin, you know. That kid would have piggybacked me all the way back to the city if I’d asked. The truth is also, sometimes it’s exhausting. I step out the door and my face feels heavy with the attention. Plus it will shift—it won’t disappear, but it will definitely change—the moment I open my mouth.

So anyway, that day by the tree on the perimeter of the parking lot, the bark gleaming with fresh sap in the outline of R J M, Rose Sr. sized me up.

“Thanks for bringing my baby back,” she said, sliding a possessive hand over Rose Jr.’s shoulder. “She’s fine now.”

Rose Sr. had clearly had a rough life. Her paper-thin skin rumpled the way super white faces do when they’ve seen some sun. She must’ve grown up in California, or somewhere sunny at least, to amass all those forehead freckles (including some suspicious-looking ones; uneven borders and a bit inflamed—hey, I read the brochures in the doctor’s office, okay?). Rose Sr.’s gray hair was home-cut tufty and she wore this kind of accidentally-

Anthropologie dress with sunflowers splattered across it. I stood there watching her for a few moments, hands hanging by my sides, sweat sliding down my spine. She squinted at me, turned Rose Jr. around and patted her skinny ass, which was a sign for the child to take off. Rose Jr. took a couple of steps towards the parking lot and bent down to shovel dust into the mesh of her ratty green sneakers. In her little short shorts and Care Bears T-shirt: oh, my heart.

“Do you have enough food?” I patted my pockets, I guess hoping to indicate via the superior quality of my clothing that I had access to non-existent resources. “Is there anything—do you need any help?”

Rose Sr. looked at me like I’d lost my mind. “I said we’re fine.”

Rose Jr. kept shoveling.

“I could—find you some water, or—” “You could just move right along.”

I didn’t want to leave. I can’t really say what told me that Rose Jr. wasn’t safe—beyond our immediate circumstances, I mean, which were obviously not without peril—or why I felt she couldn’t trust her mother. The best I can offer is that apart from her obvious distaste for my face and her evident struggle in keep- ing up with reality, Rose Sr. reminded me of my own mother. I mean not in looks or circumstance—my mother is sleek, a lawyer, with aristocratically gray hair and a widely respected, dead hus- band—but in the kind of coldness, disregard she had for her kid. Who sends an eight-year-old off alone to throw up in a crowded rest-stop bathroom? (Who sends a bed-wetting ten-year-old off on her own to a three-week summer equestrian camp? Refuses to come to the phone when the kid finally convinces the staff to let her call home? Says the experience will toughen her up and teach her how to get along in the world?)

Asshole mothers, that’s who.

It’s not that I didn’t, in the end, give my mother almost as good as I got. I bit the therapists she sent me to, and if I learned that I’d been referred through that carefully curated professional network of hers, I made sure to draw blood. All I ever wanted was a bit of love. Lord knows she gave it out enough at her ladies’ power lunches, on and fucking on about degrees and awards and remodeled kitchens with those big fucking elephant-trunk faucets or whatever. I swear to God once a week she sat me down and gave me The Talk: all my genuine advantages and it was so important not to throw it all away. You know what I think? When I was small and beautiful she could pass me around like one of her awards, shiny and decorative and testament to her brilliance. When I was older I started to fail. And learned to bite.

In any event, that first night at Vista Views all three of us— we were a kind of group, Rose Jr., Rose Sr., and me, even though I’d had to leave them by the carved tree hours ago—went to “bed” hungry and confused. I picked out my bit of dirt, lay down and got that kind of whoop feeling in my skull. You know, the sensation that reality has just smacked you in the side of the head? It wasn’t like my actual thoughts had changed. As far as my conscious self was concerned I was still in the huh-what- the-fuck phase. But my reptile brain had hit the red-alert button: i.e., a panic attack. I had been getting them since Uncle Simon’s SUV clipped me on my fifth birthday. I’d had one of those cakes that looks like a ballgown skirt with a doll’s torso on top, and there’d been a bouncy house as well as low-sugar party favors for my guests to take home. Unfortunately Uncle Simon was (is) an alcoholic, and partway through I noticed him leaving (he was just going to buy more beer), so I ran out to give him his bag, and we lived on a slope, it was a very nice Boston street, and the car clipped me on the leg and then clonk on the side of my head. It wasn’t his fault, he was drunk, and my kid-skull was barely dense enough to make a sound. My mother found me lying on the grass, my head going whoop-whoop-whoop. Hello panic. She drove me to the hospital and considering her position and Uncle Simon’s employment situation we kept it to ourselves, told the nurses some story about a loose bit of garden equipment and he paid for my first year at Bard.

So anyway.

I lay on the dirt in the dark, brain going whoop and failing to tune out the people around me whispering and crying and saying impossible things like, “Really we should be grateful” and “All I want right now is peanut butter ice cream.” By morning, tears had plastered dust on my face and my clothes were crunchy from the sweat-mud that had gathered under my waistband, around my neckline, and cuffs. I dug in my pocket for a tissue, and that’s when I found the chewing gum, manufactured and soft inside its white paper wrapper. I held the pink strip of it between my filthy fingers and admired the pillowy softness, the uniform dusting of the fake sugar, the subtle striations down its length. It had come from a long strip of other extruded gum, but right then it was a precious individual, a saliva-inducing tooth-soothing thing that I chewed for a couple minutes before it occurred to me I might have shared it and by then it was too late because I’d swallowed it.

After draining the teacher-lady’s mini water I headed towards the bathrooms. A lot of people were still asleep. A handful of MusicMovers were curled in a hemp-filled clump near an overflowing trash can. One woman—I shit you not— clutched a tambourine to her chest, held it there hard as a teddy bear. Janine and James were sitting nearby, cross-legged in the dust, facing each other, foreheads touching. Janine was looking at her phone screen like she wanted to eat it. I edged over towards them, thinking I might tell Janine that since there was no cellphone signal, it was possible her family were out there and doing just fine, eating cookies or whatever, or if they were dead their father was probably with them. But James saw me coming, gave me a fuck-off look. Okay, sure. I went around the line of community college kids—the way they were laid out, they looked almost like a long-jump dare—and refilled the mini bottle at the bathroom block. I had this happy thought of finding Rose Jr. cozy in one of those bright-colored hammocks that people take to parks, wrapped in a sleeping bag and with something precious in her fist. I didn’t care what it was, as long as it was special to her. The picture in my mind, it made me smile, so naturally enough when I saw the reality—stretched out, starfish-like, on clumped grass, no mother in sight—I was sad. Her mouth was just a little bit open and she twitched her nose in her sleep. Elbows, knees. Lumpy as beads on a string. I woke her gently and she looked for a second like she was going to punch me. She sat up and took the water bottle. I said, “Hey, let’s go out for a walk,” and she said, “Sure.”

She didn’t ask where we were going.

I took her to the main part of the human clump. She sipped at the water, carefully screwing the lid off, then back on. We stood there a moment, the two of us. Not quite touching. I hesitated about asking the cops for food, since I didn’t know what kind of stuff her mother might be into. One of the bus drivers was nearby, so we went over and I asked him, in case, you know, he had some extra stuff packed in his bus. He looked at me a beat too long and then at Rose and shook his head, no. I’m pretty sure he did have stuff in there, because when we left he was staring at the bus door. I felt like a heel for not sharing the gum. But Rose seemed happy with the mini water. I noticed a gray haze wisping up from the direction of the city, took a deep breath and gripped Rose’s hand. Her skin-grit was soft and dry.

We were wandering past a group of management consultants (their suit pants thick with dirt) when three cops gathered at the center of the temporary fence. The middle one stood with her feet planted wide, shoulders squared. She brought the megaphone to her mouth.

“Ladies and, uh … hello,” she said. Her voice scratched through the speaker. “Please continue to be patient.”

Two hundred grimy faces turned towards her, waiting. Well, good for us.

She had nothing more to say.

It wasn’t until that afternoon that I seriously considered stealing Rose. Well, taking care of her for a while. Somewhere safe. By what should have been dinner time, we were seeing the beginnings of factional clumps—as I said, up till then, there hadn’t been much of a system in place. You could feel the collective heart rate rising, getting jagged. Some festivalgoers had joined up with a few of the community-college kids to make a backpack wind-and-weather barrier over by the trees. This was smart because the day had been warm. I mean we were all root-less without access to a weather app, but it was June, so we could easily have been heading for some days in the high 80s, or hotter.

Another group had set up a tent in the middle of the parking lot rotary—those baby boomers, I guess they go through life prepared—and were sharing the space with a few of the management consultants, who sweated through their white shirts but exuded a semi-soothing sense of being in control. That group was taking turns (I swear, it was like they had a roster) to lobby the megaphone cops for food and situation updates. Their optimism was irritating. The sanitation people had split into groups by gender—yes, women manage trash too—and appeared to be drawn to the spaces nearest the buses. The drivers kept to them- selves, stayed near the cops. My fellow BioMoodMed-ers were scattered across the encampment.

Rose and I wandered through the goldening light, and I told her stories. Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty, The Three Little Pigs. Pretty sure I messed up most of the action, but she didn’t seem to mind. She listened with one ear cocked towards me, eyes focused forward, tracing the path, the horizon, the crowd. Little pig, little pig, she echoed under her breath, and then did these big melodramatic huffs, panning from left to right, ha ha, blow it all down.

She had to let go of my hand for those parts, but I didn’t mind.

If by that point my stomach had that hollowed-out, hungover feeling, it was fair to assume other people were hangry/desper- ate too. Certainly it wasn’t any place for a kid. Rose was about to see adults be crap not just as individuals, but en masse. Because hanging over the top of all those smaller groups was this grow- ing tinder-spark of a divide: the panickers versus the deniers.

Some of the panickers had already disappeared, run into the woods behind us, presumably thinking they were going to walk all the way to the city. Or away from it. (Whatever.) One woman had run at the cops and got cable-tied for her trouble. James, clearly a born panicker, was edging with his bloodied ears to- wards the perimeter every now and then. But his dog-eyes drew him back to Janine, who had wrested control of her emotions

and was taking on a leadership role with some deniers. That group was a mix: two sanitation workers, a single baby boomer, two management consultants, a handful of BioMoodMed-ers and Colin. They had arranged a circle of stones in the dirt, even put some wood in there, as if they were going to light a fire (and cook what? the dead rat from under the bin?). Rose and I edged over. Janine was talking through wet teeth about how employ- ers were going to need to rally resources for employees in the weeks and months after the disaster. Janine—who had stuffed her phone visibly in her cleavage—jabbed her finger at the dirt and said all companies would really need to step up their game on childcare. BioMoodMed had made all these promises when

they’d hired her. She drew a map in the dust, demonstrating how BioMoodMed could fit a day care between accounting and pro- curement. “We don’t need a goddam staff lounge,” she insisted. “We need affordable, accessible childcare. For all.”

The members of her group nodded and Colin gazed up at me with puppy-dog eyes.

I’ve never been great at groups. It’s not only that I struggle to relate to people, although they are confusing (I could set aside time each week just to wonder at the fact that How are you is not in fact a question). It’s this gathering thing. It’s unnerving even in normal times: one minute you’re all a collection of bodies inhabiting the same space, and the next you have needs in common, and somehow from that you’re meant to magically enjoy the same stuff. Not only that, but you’re supposed to agree that the world is more one way than another—and that this is either exactly right or an utter disaster. What the fuck? Now you’re all on a boat rowing urgently upstream or cheering on the goddam Red Sox as if you knew a single actual individual player out there on the distant field, invested in the emotional truth of how some dude swings a stick at a ball. As if you could actually be in his mind in that moment, feel it with him. But you’ll lose interest in that asshole the minute he misses a hit, or swings the wrong way, or you have to get home to take a shit.

The truth is I’m not so great at individuals, either. But for Rose I was determined to try. If the cops were still a no-go, I

figured we might attempt the next-best thing. Those baby boom- ers had brought a tent, maybe they had some snacks too. I mean the fact that the management consultants were near the en- trance to their tent—like sentries of corporate America—did not inspire a whole lot of confidence, but then again, white-shirted young men were my core demographic. I took Rose’s hand, light as a feather against my palm, straightened my shoulders and calibrated my smile. “Hey there,” I said, doing my best to sound soft and unaware of all the stuff that was going on with my face, “How are you guys doing, Rose here and I, we were just wonder- ing, um, if you—”

From inside the tent, the opening lines of “Sweet Caroline.” The singers were a mix of men and women: a single soprano, by the sound of it, the rest of them tenors. I mean they weren’t professionals, but they knew what they were doing. They nailed that song from the get-go: where it began, with that lilt on the n, and just like that for a moment I was back at Fenway, ten years old, swaying along to Neil Diamond and my mother, even my neat-and-tidy mother, belting out the words. It threw me off, to be honest. A lot of strong emotions slung through my body and I forgot, for a moment, to keep my face all I don’t know I’m beautiful. Management Dude Number One shrugged towards the tent and looked back at me confused, while Number Two took a seat on the little camp chair, chewing on something he pulled from his pocket. I rearranged my face and turned to Dude Number One and said, “It’s just that Rose here and I, we’re hungry. We could really use some help.” You could see he was relieved, this was a script he knew, this was a face belonging to a body he wanted to … well, I didn’t feel right about finishing this thought, given Rose was standing right there. The singers were belting out the chorus and Dude One’s expression softened and he said “Yeah, I know, it’s terrible isn’t it” and then he made a face that sug- gested he’d go inside and ask the boomers but didn’t want to interrupt their song. They were really sticking with the script, going the full three minutes and so we just stood there smiling at each other. I knew better than to say any more word-like things that would jeopardize our chances of getting food.

Finally, the song stopped and Dude One went in, leaving us with Dude Two, who glanced briefly at my breasts before taking another bite of what I could now see was beef jerky. Dude One tried to speak in a low voice but of course we could hear every word. He asked them if they could spare anything at all; they said who for; he said a woman and her kid; they said well maybe, of course; they rustled around with some plastic; Dude One came out with a crumpled brown paper bag and thrust it at me while Dude Two got up and took his turn to pester the cops. Rose grabbed the bag and said “Thanks” in the sweetest little- girl voice I’ve ever heard. Dude One opened his mouth and then closed it again. From inside the tent, the opening lines of “Song Sung Blue.” Rose and I beat a quick retreat.

The bag contained three saltine crackers and about a quarter cup of trail mix. I took three almonds and gave the rest to Rose. She wolfed that shit down, straight from the bag to her mouth.

I wondered if there was a thing about telling kids not to eat too fast, or encouraging them to share or save some for later, and then I remembered we were stuck at a rest area during what might well turn out to be the end of the world, so I left her to it. My stomach clawed at me and I tried to think of it as an opportunity for weight loss. I wasn’t much convinced but my belly was very f lat. You have to take the wins when you get them, celebrate every victory, as my mother likes to say.

Somewhere around dusk the wind shifted enough that we could smell fire from the city, that acrid smell of burning buildings. It felt unfair, this intrusion of definite destruction. Doom, doom, beat my heart (over the top? Maybe. Accurate? Yes). As the plume darkened and blanketed half the sky one of the panickers (a boomer wearing a flannel shirt) detoured from his perimeter run and headed for Janine’s group. A shriek went up as the man’s bare feet barreled through the dust.

“Calm the fuck down!” shouted Colin, standing in front of the group, arms folded across his soup kitchen T-shirt. Oh, the baby, he wasn’t nearly tall nor heavy enough to pose any barrier to Mr. Crazy Panicker and his momentum. Colin went over quick smart, his sneaker soles rising up into the air, his ass sliding into the dirt.

Now Janine stood, arms in the air like some kind of calisthenic traffic cop, shouting, “WHAT are you doing?”

The guy stopped, of course, because Janine is a woman and white. Mr. Panicker stood there like a block, his body all tense, fists clenched.

“Calm down,” Janine shouted. “There is no need to panic.” “Fuck you,” the man bellowed, “there IS.”

They were maybe three feet apart. The cuff of the man’s pants rested uncertainly in the dirt. Bow-legged. Afraid.

“Just-take-a-look at what’s going on around you,” the man said, briefly taking on a podcaster tone. “It’s too late for PTA meetings, too late for hope.”

You can see the problem. People adapt differently to new information. In ideal circumstances, we need time to rearrange the frameworks. While things are still wavering—until reality has snapped to grid—we cling to that first gut reaction. We’d had, what? a day? And although a lot of people would say the warning signs had been flashing, well and truly fucking blaring, for years if not decades, the truth is that until you’ve passed that bright invisible line, other realities, better, nicer outcomes, are still possible.

Mr. Sir Panicker was having none of it.

“You all have to wake up,” he shouted. “Sitting there calmly like goddam sheep, with your—with your stone circle and your invisible dinner.”

“We are awake,” said Janine, taking on a mommy tone. “We are simply trying to take care of each other. When we—when we get home, we are still going to need strong institutions. Jobs to go to. Think how grateful we are going to feel, for supermarkets, for drivable roads. Schools, and—”

“Fuck your, fuck your SCHOOLS!” the man shouted, and I gripped Rose’s hand extra tight. “You can take your sweet-lady- ass gratitude and shove—”

Colin leapt up and tackled the guy to the ground. They scuffled, belly to belly, grunting and grabbing each other’s forearms, wrists, chins. Their dull almost-blows reminded me of plasticine.

After a few minutes of this the cops showed up and pulled their guns, like they’d done the math and realized that there were ten of them, two hundred of us. The boomer crawled up out of the dirt and let out a tearing sob. A cop grabbed his wrists.

“Come on, man,” the cop said. “Let’s go somewhere and cool off.”

Janine slipped her suit jacket around Colin’s shoulders and held him, arms outstretched, in the parental posture of there now. Over by the police cruisers the cops made a show of giving Mr. Panicker the low-and-stern talk. Palms rested, fingers twitched over the dark places where their guns nestled.

That night I settled myself closer to the Roses, about five bodies away, close enough that I’d hear Rose Jr. if she called out in the night. The stars were stupid sparkly in the half-sky. I brushed some stones out from under the small of my back and thought about my mother, who as you have most likely intuited I did not much like and who, I am certain, never liked me. You’ll want me to blame her for this, to get angry and cry, say that I never had a chance to grow properly because I was denied her love and attention as a child. But think for yourself a minute.

Maybe I’m just a jerk. Maybe she was depressed or otherwise broken, maybe she got a class four tear, which means, all the way from vagina to asshole, when I came of her twenty-eight years ago. You don’t know. I haven’t told you enough that you can judge.

What I will say is that people are hard work.

In and around that parking lot an hour’s drive from the city, two hundred people tried to figure out how to wait, or survive, or sleep, or something. I gave up on rearranging the stones and crept over to Rose. Her head rested next to my elbow; I took off my shirt and draped it over her small form. In my mind I floated out over all those humans. Glowering. Crying. Dreaming.

The cellphone networks came back up early the next morning. People rushed the buses to take turns with the charging stations, clutching their screens, laughing, screaming, crying. The cops moved with fresh purpose, their radios crackled, they slapped each other’s shoulders. The college kids hugged and cried, blasted dance music on their phones. Janine crouched in front of one of the bus wheels, her face frozen. I sat with the Roses and took it all in. It was Rose Jr. who took my hand and led me towards the buses so I could charge my phone. She lay on one of the seats, twirling her legs in the air,

while my phone woke up. The dusty screen swarmed with news alerts and emergency notifications. Gray rectangles clamored over one another, full of yellow exclamation points and words like DESTROYED and TOLL. I realized then that I did not want to know what had happened. I wanted for it all to have un- happened. For the Earth to suck everything back into its own mouth and for my friend Jane, the only one who had messaged me, to be telling me something other than that her two-year- old’s leg got busted by a falling tree.

Outside the air began to thud and we realized—look, see, on the horizon—a helicopter was coming. Rose and I ran out with the crowd, hands up, fingers splayed. They threw us bottled water and protein bars and it all tasted good and sweet. I gulped and peeled salty skin off my lips. With calm but pleading intention I arranged my face and pulled Rose to the front of the crowd. They were going to choose us, me and Rose. I knew they would and they did. It was too loud to hear much of anything and I saw Rose’s mouth moving but I just pulled her closer, those little bones, we’re going to be okay I shouted and lifted her up onto my hip. She weighed almost nothing and her breath was hot on my shoulder and then there was this sharpness that clamped. Reflexively my arm released. Rose slid to the ground and in the second I had to glance at my shoulder—bite-shaped blood soaking through—she was gone. Lower, deeper into the crowd. Rose, I cried, and in the excitement one sanitation worker saw us get separated, her face registered my pain in an open-mouthed O and then she got pushed out of view. One of the helicopter guys, so robust in his clean black flight suit, held his hand out to me. I pulled myself into the chopper and he boosted me up, his palm to my waist. All these imprints on me, points of contact. I clicked the buckle and tightened my harness. The rotor thundered and the trio across from me (one boomer and two community college kids) tried to make eye contact. I turned to the window.

From the air, two hundred dot-like faces. A swinging bridge.

Bulging streets.

I jammed a peanut butter Lärabar in my face and gagged gently on joy. The helicopter listed to the left, pulled us towards the water-blue sky.

Mine was a complicated satisfaction.

Marching Band - Tiffany Hsieh

Here they go with Fred driving the stick shift home, Kim driving the family van home, Jerry driving the wedding coupe to his honeymoon home, and Jenny driving a rental away from home via the Chi-Cheemaun Ferry. Kim in the van is following behind Fred in the stick. The stick’s swerving and spinning across all lanes and back and Kim’s thinking there goes the husband to the stick, goes the son to wedlock, goes the daughter to the Chi-Cheemaun. Kim’s saying this to Jenny on the phone, the way she typically is with her doomsday voice. Jenny in the rental on the ferry is picturing the airbag exploding in Fred’s face. She’s thinking that’s that, party’s over, turn around and, what, go home? Where’s Jerry? Where’s Jerry every time?

Fucking weddings. Finally Kim’s saying thank God it’s just the stick but Jenny’s unsure what God’s going to do with a thing like a stick. The ferry’s docking and wheels are coming out of the vessel’s belly like a marching band. Jenny’s starting up the rental. Jenny’s idling. Jenny’s rolling. Jenny’s roaring.

Funeral Preparation - Lucy Zhang

I ask Ren to carve a peace symbol into my tombstone even though we’re the same age and Ren is more likely to die earlier than me given Ren’s maotai problem and resistance to exercise to which I say, you can’t predict bad luck and I’ve always had bad luck, which Mom claims is because she gave birth to me upside down even though natural-birthed babies are supposed to emerge head first out the vagina, popping like bubble wrap, the harbinger of all the misfortune I’d bring, and yet you kept me,

I tell Mom since she complains a lot for someone who could’ve left me with my grandparents and their flock of pigeons and oily, pigeon noodle soup, grease gripping the xian mian like super glue, flipping my stomach until I barfed, because making peace means ignoring all those nitty gritty details, even the blow- horn-blaring ones Ren says will one day kill me—biking down hills without breaks, ice skating on lakes that haven’t frozen over completely, hopping in local strangers’ cars who offer meals at their houses—which is why I’ll die first even though I eat all of my bok choy and Ren gorges on Popeyes, although perhaps not yet, not until I’ve found a nice plot of earth to stick a stone and a pretty jar for my ashes, prepaid with my card so no one gets lazy because “she’s dead, she’ll never know,” a first and final resting place for after I eject an upside down baby, after Ren drives me to the grocery store so we can pick up daisy leaves and shoots as I wait for an opportunity to unearth all the pillbugs in the backyard with my fingers, clawing through the soil like those bird women who are too ugly to bare their faces.

Freedom - Laura Farmer

The day my girlfriend Shenandoah went missing, Nate and I’d started drinking early. It was raining—hot, summer rain—and Nate and I put together some homemade rain gear and trudged our way to the store to get beer. By the time Shan got home for her lunch break we were laid out on the couches, ready to take naps for the rest of the afternoon. Plus, it was still raining. It was like the outside world was encouraging our behavior.

“Look at you,” Shan said to me. “Are you naked?” “No,” I said, rustling around. “There are shorts on.” “It’s not even noon.” She shook her head. But she was

laughing. My girl. “I haven’t even eaten yet.”

“Are you hungry?” Nate asked. Shan sat down next to me on the sofa. She touched my arm, I remember. “We went to the store,” Nate finished.

“It’s a rain suit,” I explained.

“You wrapped yourself in an old plastic tarp.”

“This is a garbage sack,” Nate declared, standing to model. “I just put holes in it.”

Nate was my oldest friend, a tall man who was up for anything. We grew up playing ball in the middle of C Ave, just a few streets over from where I lived now. He was the guy who would come over at seven in the morning, or two in the morning, if you said you needed him or promised it would be fun.

“Okay, Chief.” He called everybody Chief. “Give me two shakes.”

Before Shan went missing, there was more going my way than ever before. Now, afterwards, I know it with this sense of hyperawareness that makes me wish I could go back. Not because I could change anything, but just so I could pay attention.

Nate turned on the television. Shan ate a sandwich, then she snuggled in next to me. She wiped water off me with a blanket.

“Can I borrow your car?” “But you’re warm.” “Where are your keys?” “Sure,” I said.

“Mine’s shaking still. I just want to make sure I get back.”

I got the keys and walked her out back. Our cars were parked side by side in the backyard, looking cleaner and shinier than ever.

“Home at three?” I asked. Shan smiled.

I gave her my keys and she got in. I was still pretty drunk at this point, but I remember she didn’t answer me, not really. She got in and put her seat belt on. It divided her breasts nicely and I looked for awhile. She saw me looking and put her third finger on her chest. She didn’t look sad or anything; she just looked like herself. But that was it.

“Okay, I gotta go,” she said. “C’mere.” She tilted her face towards me.

After she drove off, I got in her car and curled up in the backseat. It just seemed like the thing to do. I lay there listening to the rain on the roof. I remember thinking how nice it would have been if Shan didn’t have to go back to work, if we could have just stayed together on the couch all afternoon. But Shan was practical. She was never late for work. She paid her bills, got up at the same time every morning. When she prayed at night— because she did—she mostly offered up prayers of thanksgiving. I’d never met someone like Shan: that grounded, that sure.

That’s why I never would have seen it coming.

When I got back inside Nate and some stranger he knew were listening to old rap albums and smoking pot. I joined in.

The man had brought more beer and we drank that too.

Other people might be working, I thought, but it’s our day off. We should do what we want.

We sat there until it got close to dinner. Then the man went home and I remembered my legs, still wrapped in plastic.

“Good idea,” Nate said as I started cutting them out with a scissors. “Want me to do your other leg?”

“With what?” I only had one pair of scissors.

Nate went into the kitchen and came back with a small knife. “No,” I said.

“It’s serrated. It won’t hurt. I’ll keep the blade up.” “No.”

“Jeez,” he said, sitting back down on the sofa. “I’m just trying to help.”

It was then that we started talking about Shenandoah. We noticed she wasn’t home when she said she would be, but now that it was after five we put it in words and let it come out of our mouths. Now her absence was loose and in the room with us. It didn’t feel good.

Shan and I had been dating for three years and had been living together for two. It had been a long time. I wanted to get married, but she’d been married before and told me to wait. Her last marriage was good for awhile, then it got real bad.

“I just want to enjoy this,” she said. “I want to make sure we’re sure.”

“That you’re sure,” I said. “We’re sure,” she emphasized.

So sometimes we were good and had Nate and his date of the week over for dinner and cards, and sometimes I did dumb stuff like wrap myself in plastic and walk to Hy-Vee in the rain. But even when Shan and I were fighting, even when we had our moments, she always came home after work.

At six I started making calls. I called her work, her girlfriends. At seven I called her folks. Nate got up and put a frozen pizza in the oven. He handed me slices while I kept making calls. At eight I called the police, who said they couldn’t do anything until more time passed.

“She’s in my car,” I said. “Does that help?”

“Do you want to report a stolen vehicle?”

“Can you look for that right away?”

“Yes. What kind of vehicle is it?”

When I got off the phone with the police I called more people: friends, family. I went through Shan’s address book and started with the people who lived closest to us, then moved further out until I was sending messages all across northeast Iowa, up to parts of Minnesota. If someone didn’t answer I repeated their number over and over again in my head and tried to picture the person in my mind. It calmed me. It made me think there were lots of people out there, all looking for Shan, all together on this rainy night.

At midnight Nate said, “All right. We got to get out of the house.”

“But she might call.”

“If she does, she’ll call back. Hell, people are going to be calling all night.”

“Where are we going?”

“Do you have her keys?” Nate didn’t have a car but he was a much better driver than me. He was careful. And right then, wearing that garbage sack shirt, he was surprisingly rational.

Shan’s car looked like it always did: full tank, clean floor mats, alphabetized music collection. I opened the glove box. I looked through her cassettes. I don’t know what I was looking for—a clue, something—but I didn’t find it.

“We’re gonna drive her route. Just look for your car, or her, or anything. She got a flashlight in there?”

She did, of course. Whenever I needed something she had it. There was sunscreen in her glove box. Matches. A deck of cards. How could she be lost? How could she not be prepared for something?

We drove down 1st Avenue, into the belly of Cedar Rapids, past the payday lending place, the rent-a-center, the gas station. There was a car in the Little Gem diner parking lot with a flat tire and a black garbage bag taped over the back-passenger window. The bag rustled in the breeze.

We pulled over. For awhile there Shan and I went to Little Gem every Sunday night. An old woman with long grey hair, Dorothy, would wait on us and I was hoping she was on tonight. She knew us.

Dorothy stopped cleaning the counter when we walked in.

She called me by name. I introduced her to Nate, who apologized for wearing a garbage sack shirt.

I told Dorothy everything. We’d never had a personal conversation before but suddenly I felt very close to her. I told her about Shan’s routine, about how long she’d been missing.

“I’m sorry, Hon, I haven’t seen her. She stopped by a couple of times last week, but not today. I’m real sorry.”

“What’s she look like?” A man got up from his booth and came over. I showed him a picture from my wallet, one I took at a barbeque. Shan hated the picture because she thought she

looked greasy, but I thought it was perfect. She was my everyday beauty.

“Nice-looking girl. You could put it up on the bulletin board with your number.”

“Have you seen her?”

The man shook his head. He called his friends over and they looked. There was a whole group of us now, crowded around Dorothy. I wanted to take them all out with us; I wanted to invite them all to my wedding. They carefully passed Shan’s picture back and forth, trying not to leave fingerprints.

Dorothy gave me a piece of paper and some thumbtacks. It was strange leaving the picture behind, but Dorothy told me there’d be people in and out all night. I’d be sure to get calls.

“Write about your car, too,” she said. “Put that all down.” “We’ll say a prayer for her,” one of the men said. Nate shook

his hand.

We stopped at every open business between home and work, talking to whoever was around. I didn’t have another picture of Shan, so Nate drew her face on the back of receipts, on napkins.

At the Sip ‘N’ Stir they let him draw her face in pen on the wall behind the bar.

“This way people’ll see her,” the bartender said.

Nate made more sketches on whatever paper people had in their pockets. It was amazing, the way he could pull Shan out of paystubs, matchbooks, to-do lists. It just took a few lines and there she was: her eyes, her hair, like that’s where she’d been hiding all along.

When we got outside it had stopped raining. Nate and I got back in the car and went past the railroad tracks, the lake, the Quaker plant that stood like a beacon in a cloud of oat- smelling fog.

“Becca went missing one time, you remember her? My old downstairs neighbor?” Nate looked over at me. He was trying.

“Shan isn’t Becca,” I said.

“She was gone for like two days.” Nate pulled onto 380 and fired through the curve. It was the middle of the night, and we were the only ones on the road. “We called the cops, her family, the whole bit, and turns out she was just over at Tony’s on a bender. She was across the street the whole time.”

“You think Shan’s just out drinking.”

“Didn’t I tell you this story? Tony was that guy who always wore overalls.”

“She’s not across some street. Something’s—” “Hang on,” Nate said. “Hang on.”

We pulled out of the bend and there was an eighteen-wheeler stopped right in the middle of the lane. Nate parked on the shoulder and a man came running over to us, his eyes wild.

“He jumped. The kid just jumped in front of me. You gotta help him.”

I’d seen dead people before, at funerals and in hospitals, but never out in the world. This was a young kid, maybe twenty, with a huge gash in his side that made him spill out over the highway like a deer. I could still see his hands, his sneakers. I just sat there in the car, looking.

But Nate got moving. He found a blanket in Shan’s trunk and threw it over the kid, then took his garbage bag shirt off to cover the kid’s hands.

“Oh, man,” the trucker said, leaning on his cab. He was shaking. I went over and sat down next to him. We just sat right down in the middle of the road.

“That’s his car there,” the trucker explained, pointing. “Kid was standing next to it, watching me come. I thought he was going to flag me down, but he didn’t so I kept going.”

The man shook his head. “But he had that look, you know?” He nodded at me, looking for understanding. “I’ve felt it, too.

That was this kid. He was going to jump but by the time I knew it my truck was right in front of him and there he went. He was timing it.”

A few weeks ago, the local news did a piece on mental health and suicide in Iowa. Shan and I watched the story, then turned the TV off and sat in the dark. We were already in bed. I told her I knew what that feeling was like.

“Well, not exactly. I’ve never wanted to do it. But I’ve wondered. Like when I get to the top of a flight of stairs, I’ll think: I could just lean over…”

“Really?”

“I’m not going to kill myself or anything. It’s just realizing I could, you know? That there’s an option.”

I couldn’t get it right. About how being on the edge of something can be hopeful. You realize your own power, and then you choose to come back.

“It’s kind of beautiful,” I said. “Coming back isn’t beautiful.” “What do you mean?”

“That’s not it. What’s beautiful is letting go. It’s letting all this go,” she waved her hands in the air. “Complete and total freedom. That’s beauty.”

It was her face that made me nervous. She was so calm, so sure. I asked if she wanted to talk about it, but she just smiled and kissed me goodnight. We never talked about it again.

Sitting there with the trucker, I started thinking Shan wasn’t missing, that she was just where she wanted to be. But I wanted to keep believing something else: that she’d been kidnapped, or was trapped somewhere, or something else dramatic and unlikely. Those options, terrible as they were, were better than the truth.

Nate paced around the body, guarding it. He had a tattoo of a falling star across his left breast and one of the Morton Salt Girl on his bicep. Out in the cold wind, they both seemed a deeper blue.

That’s when we heard sirens, saw the blue and red lights off in the distance.

I patted the trucker on the back and he nodded. He nodded again and again.

“I know,” he said, like I’d told him something. He wiped his face with his sleeve. “I know.”

Ordinary Ghost - Michael Alessi

Our father is gone, but for some months his arms haunt the apartment, thumping about like two dachshunds. It must be the rest of him can’t hear us calling them to heel, or that the dead receive new names somehow, so the arms go on toiling at his old chores—sanding the cat’s claw marks from the buffet, unclogging a slow drain—with thumbs blackened by their own blind hammer strikes. For weeks his arms are simply a tripping hazard, until one day we come home to find the kitchen sink taken apart, its pipes littered across the tile like some child’s train set. Decanters tumble. The cat’s tail goes missing. We hope they’ll retire, but come spring the arms scribble at his desk, incorrectly filing the family taxes. How difficult to say no thank you to deaf hands, but we do our best spraying them with water. They seem frightened wet, perhaps because we know he never learned how to swim. Once we put the sink back together, bathing his arms turns bloody. The faucet sputters worse than before and the limbs flail blindly to shut it off, often hooking us with an elbow or knuckle. We only do it because of what happens afterwards, when our father’s arms turn docile, cocooned in towels, and for a short while we can hold a part of him. In the end, he becomes an ordinary ghost, as present and distant as air. These days, you can find one arm sporting an orange apron, selling bolts at the hardware store across town. The other moved to Wisconsin, where things are more German.

The Manic Pixie Dreamgirl Stops Dyeing Her Hair - Michael Czyzniejewski

For once, she wants to meet somebody who’s just as interesting as she is.

She’s tired of pulling meek loners and aspiring sociopaths out of their shells. She’s tired of adding zest to lives. Of rescuing saps from doldrums. She wants to meet someone at a good place. Someone not in crisis. Someone at the start of their rope instead of its end.

She wishes she could stop attracting these figures altogether, but they find her like a bad cold. She’s not looking for a project, yet at every turn, there he is, a puppy in a rainstorm, scratching to come inside. More often than not, before she realizes what’s happening, she’s Just what the doctor ordered!

She has no desire to be philosophical. Or profound. Or for her wisdom to come off as surprisingly practical. Or clever. Or out-of-the-box. Why not simply wise?

She’s tired of the phrase Live a little! She’s tired of unorthodox for unorthodox’s sake. She’s not interested in anything too normal, but once in a while, she’d like to fit in.

She wants more than a brief scene that explains her backstory, some trope built on a cliché hammered together by typecasting. She doesn’t mind the awards buzz, but is secretly disappointed it’s for Supporting instead of Lead.

She’s had her share of bad relationships—there’s that backstory—but it doesn’t mean she has to settle.

And she certainly doesn’t want to be as saved by the encounter as the schmuck she’s saving. How does solving his problems make her life any better?

Some of this is on her, she knows, how she projects herself. There’s no reason, at her age, to dress like she does. What’s with all the flair? Why so much jewelry? And so many tattoos! Her normal hair color is blond—the one everyone wants—but it’s been tangerine with blue streaks more than half her life.

Then there’s her apartment. Above an exotic pet store? What adult actually chooses that? And her décor? Picture frames without pictures. Drapes made from concert tees. A kiddie pool filled with goldfish in the middle of the living room. Lava lamps. Alphabet magnets. Foibles the pet hedgehog. What is she, nine?

She wants to wake up, put on clothes, and get on with her day. Live her life. Be a functioning adult. But as soon as she sets foot in public, there he is, some lump of meat staring at her, shuffling over for a nervous chat. If she runs away, another man, a different lost soul, presents himself. There’s always another around a corner. Or in a shop. On a subway car. She thinks they might outnumber the rats.

If she locks herself in her apartment, men knock on her door, their cars broken down outside, their cats missing, asking if she’s registered to vote. She believes she has a homing beacon inside her, or maybe she gives off a pheromone—she’d say “magnet,” but it’s not like her, no matter how hard she tries, to be cliché.

It saddens her, to her core, she cannot escape any of this. It is here fate. It’s her curse. It’s her new idiom.