New technology developed at Ohio University outperforms standard bone density test to assess osteoporosis risk

A study recently published in the “Journal of Bone and Mineral Research” shows that a technology developed at Ohio University may do a better job of identifying older women at risk for broken bones than the current standard bone density test.

For years, doctors have used a scan called DXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) to measure bone mineral density (BMD) and assess osteoporosis risk. However, more than 75% of people who suffer fractures from simple falls do not meet the official definition of osteoporosis based on this test.

“Our current standard test misses far too many people who are at risk,” said the study’s lead investigator, Brian Clark, Ph.D., professor of biomedical sciences at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Osteopathic Heritage Foundation Harold E. Clybourne, D.O., Endowed Research Chair, and director of the Ohio Musculoskeletal and Neurological Institute (OMNI). “We’ve known for a long time that bone density doesn’t tell the whole story about bone strength.”

The research team studied 372 postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 80 across four U.S. research centers. Of those participants, nearly one third had experienced a low-trauma fracture after age 50, the rest had not.

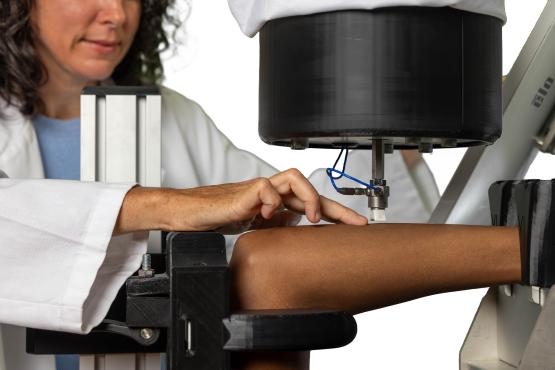

Researchers compared DXA scans with a newer, noninvasive technology called Cortical Bone Mechanics Technology (CBMT) developed at Ohio University. Unlike DXA, which measures how much mineral is in the bone, CBMT measures how strong the bone is by testing how well it resists bending. This measurement is known as “flexural rigidity.”

Women who had experienced fractures showed about 22% lower bone rigidity compared to women without fractures. The CBMT test was significantly better at distinguishing between women with and without prior fractures than DXA.

“Instead of just measuring how dense your bones are, we’re measuring how strong that bone actually is,” Clark explained. “Conceptually, that gives a much clearer picture of who may be at risk for breaking a bone.”

One of the most important findings was that the new technology worked well even in women whose DXA scans showed “normal” bone density.

“That’s the big gap in osteoporosis care,” Clark said. “Many women who break a hip or another major bone were told their bone density was fine. Our technology was able to detect weakness in many of those women.”

Clark said the research represents more than 10 years of engineering and clinical work. The new technology is now part of a medical technology startup connected to the university’s Innovation Center.

“This paper is the result of over a decade of work and a major investment from the National Institutes of Health,” Clark said. “It’s incredibly rewarding to see the technology outperform the current standard of care.”

Researchers say more studies are needed to test the technology in broader populations, including men and people from diverse backgrounds. However, the results suggest that directly measuring bone strength could improve how doctors screen for osteoporosis and identify those at risk for fractures. Because the new technology is noninvasive and radiation-free, Clark said, it is a viable option that can easily be integrated into clinical practice.

“Our goal is simple,” Clark said. “We want to identify people at risk before they break a bone. If we can do that more accurately, we can prevent suffering, reduce health care costs and help people stay active and independent longer.”

In addition to Clark, the research team included Todd Manini, Ph.D., at the University of Florida; Janet Simon, Ph.D., associate dean for research and associate professor at Ohio University College of Health Sciences and Professions; Leatha Clark, D.P.T., research assistant professor at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine; Charalampos Lyssikatos, M.D., at Indiana University School of Medicine; and Stuart Warden, Ph.D., at Indiana University School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences.

The study was supported in part by a multimillion-dollar grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIH R44AG058312). Study activities at Indiana University were partially supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (P30 AR072581).